PART I OF A MOVIE REVIEW

SURFACE

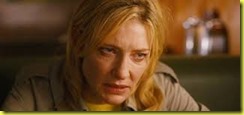

Woody Allen’s new film Blue Jasmine is everything claimed for it. Cate Blanchett’s performance, as an upper-class woman losing all, is superb. She dominates the screen every moment she’s on it. More, Blanchett is backed by an able supporting cast. Sally Hawkins as Jasmine’s sister; Alec Baldwin as Jasmine’s ex, could scarcely be better. When a friend told me Hawkins is British, at first I didn’t believe it, so well does she fit the part laid out for her.

The plot is a take-off on “Streetcar Named Desire.” An elegant woman, down on her luck, fallen from substance, moves in with a low-rent sister and her raucous environment. In this case the setting is San Francisco—a gorgeous city in which to fall apart. Director Allen cuts back and forth between present San Fran and Jasmine’s past in Manhattan and the Hamptons, presenting the background to Jasmine’s horrifying collapse.

Woody Allen is an ensemble director. Which means, of all movie elements, from plot to music to look, his films depend most on the performances of the actors inhabiting them. Allen hands his performers a forum in which to perform.

Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects, for example, is an ensemble movie. So is Blue Jasmine.

When the main character in such movies is weak, the movie is weak. Think Owen Wilson in Woody Allen’s underwhelming Midnight in Paris. Wilson’s vacuousness leaves a vacuum at the center of that film; a gaping hole which all the plot gimmicks in Allen’s narrow New York imagination can’t fill.

Happily, Cate Blanchett is not Owen Wilson. The lady can act! Blue Jasmine is a showcase for Blanchett’s startling talents. Best performance of the year? Too limiting a concept. Of the past five years? That she’ll receive the Oscar is a given. It might be the first unanimous vote.

In sum, this is the best Woody Allen film in years. Probably in decades. Allen has the rare ability, when he’s on his game, to make his films both funny and sad. I laughed throughout. The situations are so comical in a Shakespearean sense—portraying the pathos and surprising tragedy of life—that often there’s no choice but to laugh.

Blue Jasmine is a very good movie. The question remaining: How good is it?

DEPTH

Woody Allen doesn’t make “great” movies. They’re seldom large. They’re not epic in scope; in music, cinematography, or relevance. Allen’s choice of music in Blue Jasmine reveals his technique: antique jazz, strumming and singing, simple and quiet in tone to allow his cast full sway. The movie is theirs. No dominating Jerome Moross or John Williams score. No David Lean movie-canvas landscapes. Allen depends on human relationships to give his films force. They’re as much drama as cinema.

That said, Woody Allen is not without tools in his cinematic toolbox. Note his use of space in Blue Jasmine. I’m sure others have remarked on it. The spaces of upper-class scenes in the Hamptons; or in San Francisco scenes with Jasmine’s new boyfriend, visually show the vast caste differences of our American world. Scenes of large residences resting on larger oceans. I was struck by this—an effect truly cinematic, because the effect can be achieved only via the size of a movie screen in an actual movie theater.

The largeness of wealth makes the sister’s modest San Francisco apartment by contrast seem more constricted than it is.

Given that this is ultra-pricey San Francisco, the sister’s apartment is impossibly roomy for a grocery store clerk. For the movie to work, one can’t ask too many questions! (“Why didn’t he do a Google search?” Or, “How is Baldwin’s fall so swift?”)

The movie is filled with plot contrivances. It’s not about believability or plot. Allen’s knowledge of how most Americans live is limited. We accept this.

Woody Allen knows the upper classes. I was struck by the difference even between the rich scheming ex-husband (Alec Baldwin) and the rich new boyfriend (Peter Sarsgaard). New Money and Old—the uncertainty of fresh income building an impressive but shaky tower able to collapse in a minute with a phone call, versus the solidity of long-time hereditary standing and sheltered wealth. Large-income Baldwin is a transparent “Boo! Hiss!” villain; the fall guy within the movie and outside of it. For the audience. For us. His character is the politically-correct target of progressive ire—as never is the refined liberal “State Department” aristocrat Sarsgaard, who glides out of the story as easily as he glided into it. Untouched. For Jasmine and for us, he’s a fantasy and sad reality both.

*************************

Blue Jasmine rises toward excellence based on its acting. While viewing the film, you think the acting couldn’t be better. Even Andrew Dice Clay in a key role. Maybe especially Andrew Dice Clay; spot-on perfect within the context of Woody Allen’s vision, as the entire cast is spot-on perfect, within the context of the fully realized vision.

Any limits to the movie aren’t with the movie, but the vision.

When you think back on the characters, you realize most of them are stereotypes. One-dimensional caricatures, which is how Andrew Dice Clay fits in so well. This is acceptable. It’s how the characters achieve their humor. They’re Shakespearean fools. Their purpose isn’t to stand out themselves, but to provide a setting for the jewel that is Cate Blanchett’s Jasmine. They’re props for her to play with and off of.

Of the supporting cast, Bobby Cannevale as the sister’s boyfriend Chili most stands out. The only one who goes over-the-top, ripping phones off walls and emoting comically for us. He’s a blatant cross between Stanley Kowalski and any Nicolas Cage role. Nothing original about the performance—likely not intended to be original. He’s there for comic relief, along with other grotesques, including a short friend of his (a young Joe Pesci) and an obnoxiously smarmy dentist.

Jasmine requires antagonists. In her present life, Cannevale’s low-rent Stanley Kowalski is it.

What of Jasmine herself? How great truly is Cate Blanchett’s performance? One for the ages?

Blanchett knows all the tricks. A beautiful voice. The ability to switch between calm elegance and troubled distress. It’s wonderful to watch—but it’s always performance. Much of its effectiveness comes from Blanchett simply mugging for the camera. Close-ups of Blanchett frowning, down-in-the-mouth, doing stage business with her eyes borrowed from Olivier’s Othello or his mad Mahdi in Khartoum. The acting is with the camera—performing for us—and Cate Blanchett does this as well as anyone ever has.

Cate Blanchett performs on a very high level. She needs to be judged against the highest standards, to see if she, and the movie, reach into filmdom’s pantheon.

That’s a question I’ll address in Part II of this review, “Cate Blanchett and the Business of Great Acting.” Stay tuned.